Grandmaster Henrique Mecking (born 1952 in Santa Cruz, Brazil) is the best world class chessplayer to come from South or Latin America. His style of play was demanding and his preparation legendary. By playing the sharpest lines and making massive physical exertions - he was the perfectionist in search of the best moves like his USA counterpart Bobby Fischer; Mecking's best games are so smooth as to appear effortless. Grandmaster Henrique Mecking (born 1952 in Santa Cruz, Brazil) is the best world class chessplayer to come from South or Latin America. His style of play was demanding and his preparation legendary. By playing the sharpest lines and making massive physical exertions - he was the perfectionist in search of the best moves like his USA counterpart Bobby Fischer; Mecking's best games are so smooth as to appear effortless.

Chess is probably one of the oldest and most famous games in the world. It is believed to have originated from India as early as the seventh century, although the exact origins of chess are unknown. Chess has appeared in many shapes and forms. Today most people play what is known as Europeans chess. Chess is a universal game - universal in the sense that it is accepted and played in every country and culture. There are many tournaments held worldwide and many more in each individual country. The basic rules of chess are simple, however to be able to play strategically and master tactics requires skill and dedication. In its modern form the game consists of an eight by eight board of alternating black and white squares and chess pieces. Each player has sixteen different pieces, which are used to play the game with. A player starts off with a king, a queen, eight pawns, and two each of bishops, knights and rooks. The aim of the game is to corner and immobilize the opponent's king so he cannot make any further moves. Modern chess is also known as the 'queens chess' as the queen is the piece with the most power. It can move any number of squares in any direction, given there is enough space to maneuver. All pieces move in straight or diagonal lines with the exception of knights. A knight's movements are similar to the shape of the letter 'L'. When the opponent's king piece has been immobilized it is known as "checkmate". Chess has many benefits and it is now being taught in many schools over the world to children from a young age. It has many academic benefits and improves ones ability and skill. Chess improves a child's thinking ability by teaching many skills. These include the ability to focus, plan tasks ahead, thinking analytically, abstractly and strategically and consider all the options before making a move. They also improve one's social and communication skills by playing against another human player. Research has shown that kids that play chess regularly have a significant improvement in their math and reading ability. Nowadays chess can be played pretty much anywhere. All you need is the board and pieces and somebody to play against. If you cannot find another person to challenge then there are plenty of computerized versions of chess. The software comes in many different versions such as 2D or 3D and with nice animated effects or just as a plain board and pieces. It is possible to play against a computer player and up the difficulty level if required. With the advent of the Internet it is now easily possible to search for many other players online whom to play against. Garry Kasparov is one of the world's most famous chess players. He is a chess grandmaster and one of the strongest chess players in history. He has the highest ranking on the FIDE listing. Ranked first in the world for nearly all of the 20 years from 1985 to 2005, Kasparov was the last undisputed World Chess Champion from 1985 until 1993; and continued to be "classical" World Chess Champion until his defeat by Vladimir Kramnik in 2000. In February 1996, IBM's chess computer Deep Blue defeated Kasparov in one game using normal time controls, in Deep Blue - Kasparov, 1996, Game 1. However, Kasparov retorted with 3 wins and 2 draws, soundly winning the match. In May 1997, an updated version of Deep Blue defeated Kasparov in a highly publicized six-game match. This was the first time a computer had ever defeated a world champion in match play. An award-winning documentary film was made about this famous match up entitled Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine. About the Author Copyright 2005 Dave Markel For more great articles about the game of Chess visit http://for-more-info.com/chess/chess-intro.html

California's Central Coast a Hotbed for Chess

California's Central Coast is a hotbed for chess. This small community has come alive in recent months with many new chess clubs and players. One key factor is the free online chess playing site ChessManiac.com. This site was started by Dennis Steele as a way to connect chess players from the California's Central Coast to other chess players in the local community. However, it did much more than this. The website has connected Central Coast chess players to the world chess community through its free internet chess server. Here is a listing of the current chess clubs in this area: Morro Bay Chess ClubPaso Robles Chess ClubSan Luis Obispo Chess Club2 Dogs Chess ClubCambria Chess ClubCal Poly Chess Club

New Chess History Site!

There is a new chess history site. ChessHistory.netThis site is going to chronicle the most interesting world chess history events. So far it looks pretty good.

CHESS-PLAYING TO-DAY (PART II)

One very satisfactory outcome of all this match-playing has been a very much wider application of the "time limit," which had only been enforced in great masters' tournaments and in isolated games of any special importance. In the ordinary way a player might take ten minutes--and as many more as he pleased--over every move; in many games he can and does still. This is all very well if you have a whole evening and a night before you, but otherwise one of two things will probably happen: either the game will result in a draw for want of time to develop it, or the faster player will throw it away in sheer disgust. After analyzing a position for any length of time, a player ought to be able to proceed for the next few moves with tolerable rapidity, and in order to prevent him from examining every possible variation after every move, the "time limit" is introduced. The standard varies according to the quality of the chess expected. In the great masters' tournaments twenty moves in the first hour and fifteen moves an hour afterwards is the general limit. In the league matches twenty-four moves an hour is the rate, and in some contests even thirty is not considered to be too fast. A "time limit" of twenty-four moves an hour means that each player has one hour at his disposal wherein to complete his first twenty-four moves, an hour and a quarter for his first thirty moves, an hour and a half for thirty-six moves, and so on. If he has made more than the required number in the hour, the time he has gained is added on to the time allotted for the next series of moves. For instance, supposing a player has made thirty-six moves in the first hour and he has a difficult position to analyze, he can if he likes examine it for half an hour, and yet will not have exceeded his limit of thirty-six moves in an hour and a half. On the other hand, should a player exceed his "time limit"--that is, should he have failed to complete twenty-four moves in the first hour, or six additional moves for every quarter of an hour afterwards--he forfeits the game. Hour-glasses or "sand-glasses" were formerly used for the purpose of measuring time at chess matches, but now specially constructed clocks are in general use for this purpose. These clocks consist of two clocks mounted on a common base, which moves on a pivot, the two clocks therefore being on the arms of a sort of see-saw. The beam or base is so constructed that when one clock is elevated it stands perfectly perpendicular, whilst the depressed clock lies over at an angle. But as the mechanism of each clock is so constructed that it only moves when the clock is perfectly perpendicular, it follows that when the upright clock is going the depressed clock is at rest. Another and more modern variety has the two clocks fixed on the same level, but with a small brass arm reaching from the top of one to the top of the other. This arm acts as a pivot, and can be brought down into actual contact with one clock at a time by a touch of the finger. When it is thus in contact, by an ingenious device the clock is stopped, and the desired result is attained. The working of the clocks during a match is simplicity itself. At the commencement of the match the hands of each clock point to twelve, then at the call of "time to commence play," the clock of the first player is started. Then as soon as he makes his first move he stops his own clock, either by depressing it or by touching the arm referred to, the same motion starting his opponent's clock; so it goes on during the entire course of the game, each move being marked by the stopping of one clock and the starting of the other. To fight for one's club in matches is one of the most pleasing of a chess-player's duties. True, there are a few strong players who invariably decline to take part in these contests, and who reserve their skill for the club tournaments. In the one case you play for the honor of your club, in the other for your own reputation. The club secretary always thinks more kindly of the man who will do both. It is no uncommon thing for a London chess-player to be a member of one or two local clubs, and also of one of the more important central organizations. In the league and Surrey trophy matches a man must decide at the beginning of the season for which of his clubs he will fight, and he must stick to his choice. Not a little friction is sometimes caused by a valued member of a local club turning up to do battle against it. But the grievance is only imaginary, for a man is clearly at liberty to join as many clubs as he likes, and to please himself as to which he will play for. Of great central clubs there are three: the St. George's, in St. James Street, S.W.; the City of London, 19 Nicholas Lane, E.C.; and the British, of Whitehall Court, S.W. The St. George's is the oldest existing chess club of the metropolis, having been founded as far back as 1845. It is the club of the "leisured and lettered" class, and from time to time has attracted to it many of the stronger university players. At one time it took the lead in London chess matters, but of late it has not been so much in evidence, and its members now mainly content themselves with quiet afternoon chess, though they occasionally still try conclusions with other metropolitan clubs. The City of London Chess Club comes next in point of age. It was formed in 1852, and at this moment stands at the very head of English chess as a great fighting organization. It is aptly named, for it is and has always been a city club for city men, busy men all--stock-brokers, merchants, lawyers, accountants, managers and others, all representatives of the busy hive wherein they toil. In every way the "City" is a great chess institution, great alike in its membership, its aggregate playing strength and its enthusiasm for the game. Its membership totals up to something like four hundred and fifty, and it is ready to play a match, one hundred a side, with any chess club or organization in the world. The quality of the play in its championship tournament, and in the first-class sections of its great winter tournament, is of the highest; and what the "old City" can do when put upon its mettle was fully shown some little time ago when a team of master players (including Lasker) could do no more than effect a draw against a team of "City" players. We next come to the British Chess Club, which was founded in 1885. The British is much less a fighting club than a great gathering-place for the wealthy middle-class chess-player, who loves his dinner as well as his game. Of other foremost clubs we may mention the Athenaeum, the Ludgate Circus, the Metropolitan and the North London, all strong and vigorous organizations, and each boasting the possession of players of great skill. To be continued... Read Part 1 --------------------------------------- About the Author This article by J. Arnold Green is from the journal, THE LIVING AGE (Sixth Series, Volume XVIII, April, May, June, 1898), which is in the public domain. Play online chess free!

CHESS-PLAYING TO-DAY (PART I)

Chess is generally regarded by the uninitiated as being the dullest and most selfish of games, an opinion which is by no means carefully withheld from the players themselves. Truly, as an amusement or a mirth-provoking pastime it does leave something to be desired, and even such a remark as "Just look at them, they have been sitting there for hours without speaking!" is often perfectly justified. It is hard to say why a quiet and unobtrusive demeanor should evoke sarcastic comment, but most chess-players become well accustomed to it, and after all the game survives. And not only does it survive, it gains in popularity year by year, and the extent to which it is played to-day as compared with ten years ago is most remarkable. Wherein does its fascination lie? For one thing, chess has the reputation of being an intellectual game, and who does not like to be the follower of that which is intellectual? It is, moreover, one of the few games in which the players find themselves on a perfectly equal footing at the start. The element of chance does not enter in; the one who plays best wins. Further, though much has been said to the contrary, the game played in moderation is a real recreation. Mr. Potter, writing in the "Encyclopaedia Britannica," puts this very well. He says it "recreates not so much by way of amusement, properly so termed, as by taking possession of the mental faculties and diverting them from their accustomed grooves." Anyone who knows what it is to have a mind worried by business or harassed by care of any description can understand the value of a pastime which can do that. But all these are the move subtle attractions to the game. The one supreme attraction is the inexhaustible beauty of the game itself. The writer has often been asked: "Don't you find that you continually repeat games you have played before?" Well, it has been computed that there are 318,979,564,000 possible ways of playing the first four moves on each side, and, play as often as you will, it is not likely that there will be much sameness about your games. A calculation as to the number of ways of playing the first ten moves on each side--less than one-third of an ordinary game--yields a modest total of thirty figures, which would convey nothing but bewilderment to the average mind. But put in another way we can dimly perceive their significance. "Considering the population of the world to be 1,483,000,000" (twenty years ago), "more than 217,000,000,000 of years would be needed to go through them all, even if every man, woman and child on the face of the globe played without cessation at a rate of one set of ten moves per minute." (Mr. Edwyn Anthony in the "Chess-Players' Chronicle," 1878). Further comment on the inexhaustibility of the game is perhaps superfluous. On the beauty of chess it is difficult to speak with sufficient reverence. It has had at least a thousand years in which to develop, and no player regards it otherwise than as perfect. The keen delight with which a hot attack is repelled is only exceeded by that which follows the discovery of a weak point in your opponent's defence, and by the joy of concentrating an attack upon that weak point and of pushing it to a triumphant issue. Only those who know can understand! No wonder that a game with such a character should be ardently practised all the year round in one way or another by players of every degree. For those who are fortunate enough to find an opponent in the home circle, what better pastime can there be? For those who can seldom find an adversary, there is the delight of problem solving, or the even more useful study of some published game. Others again can fight a distant opponent b correspondence; while for those who wish to do battle more promiscuously, there are chess clubs and resorts innumerable. To such an extent has chess developed in popularity during the last ten years that the number of recognized chess clubs in London is about three times what it was in 1887, and cannot now be far short of 120. This is without reckoning the numerous chess clubs which form adjuncts to various institutions, such as political clubs, working men's clubs, church institutes and the like. And London does not stand alone in this respect. In the provinces a similar increase has taken place, the number of clubs having risen from 180 in 1887 to at least 420 in 1897. An equally significant fact is that the average membership has also rapidly grown, showing that the new clubs have been called into existence by the popular demand. In the early eighties there was very little inter-club organization either in London or the provinces. In the metropolis a few club matches were played, but the only one of much importance was the annual encounter between the St. George's and the City of London Clubs. Then the offer of a cup, called the Baldwin-Hoffer trophy, after its donors, induced six or seven of the stronger suburban clubs to enter into rivalry one with another. This was followed by the institution of the Surrey trophy, to be competed for by the Surrey clubs only. These competitions infused new life into the clubs, and developed a desire for regular inter-club competition within the metropolitan area. This was duly arranged in 1888, the clubs being divided into two classes, senior and junior. Five years later a still further step was taken by the formation of the London Chess League, and the organization of a yearly contest to be played in three divisions, A, B, C. The clubs in the A division have to furnish teams of twenty players, in the B division twelve, and in the C division eight. This competition has proved to be a great success, and in the present season, 1897-8, no fewer than thirty-three clubs are taking part. Naturally the interest centres round the struggle for supremacy in the A division, where the chess played is of a very high order, many of the games on the top boards being worthy of the foremost masters. To be continued... -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- About the Author This article by J. Arnold Green is from the journal, THE LIVING AGE (Sixth Series, Volume XVIII, April, May, June, 1898), which is in the public domain. Play Online Chess Free!

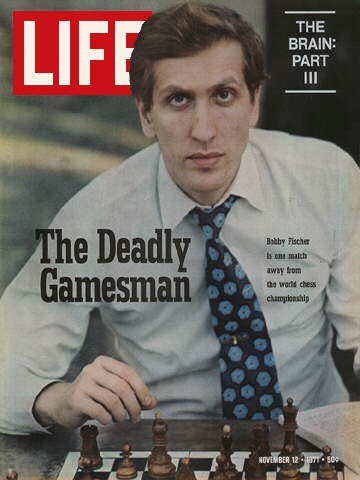

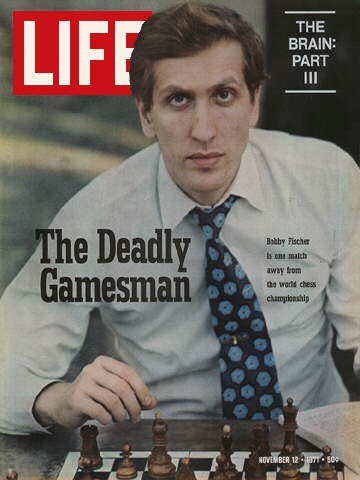

The Fischer King

In the surreal setting of war-torn Yugoslavia, reclusive chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer emerged to meet Boris Spassky. In the surreal setting of war-torn Yugoslavia, reclusive chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer emerged to meet Boris Spassky. At about 3:30 PM on Sept. 2, Bobby Fischer shook hands with Boris Spassky over a chess board in a hotel conference room on the Adriatic coast of Yugoslavia, then quietly pushed the white's king's pawn two squares forward. Fischer has always preferred the king's pawn opening-he has long touted it as white's best first move-and let history note that it may have been the only predictable act to Occur so far in this match, and through all the days leading up to it. Indeed, it came as part of a scene so surreal as to suggest no less than a dream. Exactly 20 years and one day had passed since the final game of that riotous summer of 1972, when Spassky, then the world champion from the Soviet Union, and Fischer, the eccentric, temperamental chess genius from Brooklyn, faced each other for nearly two months across a chess board in Reykjavik, Iceland, fighting for the world title in an internationally celebrated match that left them as symbols of their time: steely cold warriors doing battle with wooden cannons in the ultimate mind game, at the height of East-West tensions. Read More...

Bobby Fischer is a Ferocious Winner

Angry voices rattled the door to Bobby Fischer's hotel room as I raised my hand to knock. "Goddammit, I'm sick of it!" I heard Bobby shouting. "I'm sick of seeing people! I got to work, I got to rest! Why didn't you ask me before you set up all those appointments? To hell with them!" Then I heard the mild and dignified executive director of the U.S. Chess Federation addressing the man who may well be the greatest chess player in world history in a tone just slightly lower than a yell: "Bobby, ever since we came to Buenos Aires I've done nothing but take care of you, day and night. You ungrateful ---!" It was 3 p.m., a bit early for Fischer to be up. Ten minutes later, finding the hall silent, I risked a knock and Fischer cracked the door. "Oh yeah, the guy from LIFE. Come on in." His smile was broad and boyish but his eyes were wary. Tall, wide and flat, with a head too small for his big body, he put me in mind of a pale transhuman sculpture by Henry Moore. I had seen him twice before but never so tired. Read More...

The Chess of Bobby Fischer

Fischer's games are so full of ideas, from opening adventures to the themes of composed endings, that they are in themselves the best introduction to the pleasures of the game. In the arduous path to chess mastery, enjoyment is the surest driving force. In the words of Bobby Fischer, "You can get good only if you love the game." So much has been written about Fischer as a personality that the general public, including the chess fraternity, has been blinded to his chess. His games have been analyzed over and over in the chess journals. He has published three books himself, with varying degrees of help from other authors. Yet his winning methods, his unique contributions to the larger body of chess knowledge, and his rightful place in the history of the game have been overshadowed by all the publicity. Read More...

|

Grandmaster Henrique Mecking (born 1952 in Santa Cruz, Brazil) is the best world class chessplayer to come from South or Latin America. His style of play was demanding and his preparation legendary. By playing the sharpest lines and making massive physical exertions - he was the perfectionist in search of the best moves like his USA counterpart Bobby Fischer; Mecking's best games are so smooth as to appear effortless.

Grandmaster Henrique Mecking (born 1952 in Santa Cruz, Brazil) is the best world class chessplayer to come from South or Latin America. His style of play was demanding and his preparation legendary. By playing the sharpest lines and making massive physical exertions - he was the perfectionist in search of the best moves like his USA counterpart Bobby Fischer; Mecking's best games are so smooth as to appear effortless.

Fischer's games are so full of ideas, from opening adventures to the themes of composed endings, that they are in themselves the best introduction to the pleasures of the game. In the arduous path to chess mastery, enjoyment is the surest driving force. In the words of Bobby Fischer, "You can get good only if you love the game."

Fischer's games are so full of ideas, from opening adventures to the themes of composed endings, that they are in themselves the best introduction to the pleasures of the game. In the arduous path to chess mastery, enjoyment is the surest driving force. In the words of Bobby Fischer, "You can get good only if you love the game."